Preventing Rickets in Infants and Young Children

Understanding Rickets: The Basics

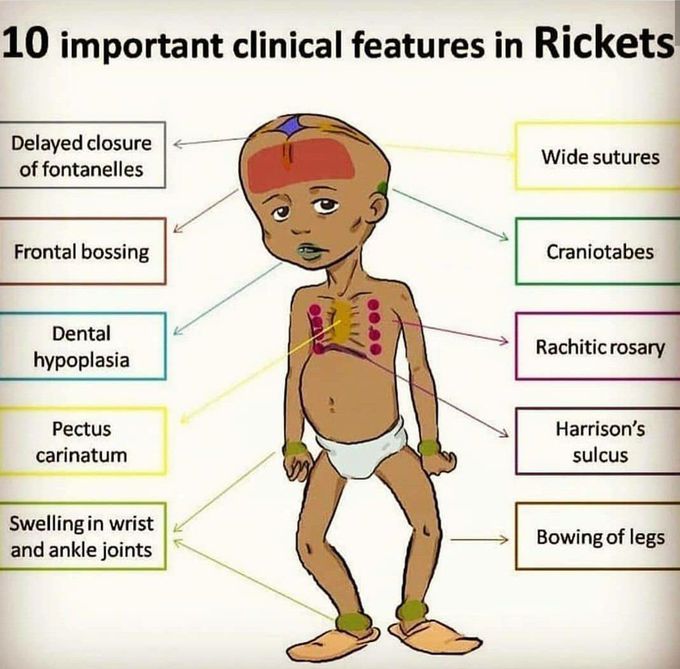

Rickets occurs when growing bones fail to mineralize properly, leading to skeletal deformities and growth problems. The condition primarily affects the growth plates—areas of developing cartilage tissue near the ends of long bones. When these plates don't receive adequate minerals, particularly calcium and phosphate, bones become soft and prone to bending under the weight of the growing child.

The most common form of rickets stems from vitamin D deficiency. Vitamin D plays a pivotal role in calcium absorption from the intestines and maintaining proper calcium and phosphate levels in the blood. Without sufficient vitamin D, the body cannot effectively utilize dietary calcium, regardless of how much calcium a child consumes.

The visible signs of rickets can be distressing. Children may develop bowed legs or knock knees, delayed growth, dental problems, skeletal pain, muscle weakness, and in severe cases, seizures due to low calcium levels. The skull bones may soften, causing unusual head shapes, and the rib cage can develop bumps where the ribs meet the breastbone, creating what's known as a "rachitic rosary."

Why Rickets Persists in Modern Times

Despite our advanced understanding of nutrition and widespread availability of vitamin D-fortified foods, rickets has experienced a resurgence in many countries. Several factors contribute to this paradox.

Exclusive breastfeeding, while offering numerous health benefits, provides limited vitamin D unless the mother has adequate levels herself or the infant receives supplementation. Breast milk typically contains only about 25 IU of vitamin D per liter, far below an infant's daily requirements.

Modern lifestyle changes have significantly reduced sun exposure for both children and pregnant women. Concerns about skin cancer have led to increased use of sunscreen and protective clothing, while more time spent indoors due to technology, urbanization, and safety concerns has further limited natural vitamin D production through sun exposure. For children with darker skin pigmentation, the risk increases substantially, as melanin reduces the skin's ability to produce vitamin D from sunlight.

Dietary factors also play a role. Some children follow restricted diets due to allergies, cultural practices, or dietary preferences that may limit their vitamin D and calcium intake. Additionally, certain medical conditions affecting the digestive system, liver, or kidneys can interfere with vitamin D absorption or conversion to its active form.

The Critical Role of Vitamin D

Vitamin D functions more like a hormone than a traditional vitamin. When skin is exposed to ultraviolet B (UVB) rays from sunlight, it synthesizes vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol). Dietary sources provide both D3 and D2 (ergocalciferol). The liver then converts these into 25-hydroxyvitamin D, and the kidneys transform it into the active form, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D.

This active vitamin D regulates calcium absorption in the intestines, helps maintain blood calcium levels, and supports bone mineralization. It also influences immune function, cell growth, and inflammation reduction—benefits that extend beyond skeletal health.

The recommended daily intake of vitamin D varies by age and circumstance. Infants from birth to 12 months require at least 400 IU (10 mcg) daily. Children aged one to 18 years need 600 IU (15 mcg) daily. However, some pediatric experts suggest higher amounts may be beneficial, particularly for at-risk populations.

Prevention Strategies for Different Age Groups

Newborns and Infants (0-12 months)

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that all breastfed infants receive vitamin D supplementation beginning in the first few days of life. A daily supplement of 400 IU should continue until the infant is weaned and consuming at least 32 ounces of vitamin D-fortified formula or whole milk daily.

For formula-fed infants, vitamin D supplementation depends on consumption. Since infant formula is fortified with vitamin D, babies drinking at least 32 ounces daily typically meet their requirements without additional supplementation. However, infants consuming less formula may need supplements.

Parents should discuss supplementation with their pediatrician during early well-child visits. Liquid vitamin D drops designed for infants are readily available and easy to administer. The drops can be placed directly in the baby's mouth or mixed with breast milk or formula.

Maternal vitamin D status during pregnancy significantly influences infant stores at birth. Pregnant women should ensure adequate vitamin D intake—typically 600 IU daily, though some practitioners recommend higher doses—to provide their babies with better initial reserves.

Toddlers and Preschoolers (1-5 years)

As children transition to solid foods, dietary sources of vitamin D become increasingly important. However, few foods naturally contain substantial amounts of vitamin D. Fatty fish like salmon, mackerel, and sardines are excellent sources, providing several hundred IU per serving. Egg yolks contain small amounts, and some mushrooms exposed to UV light offer plant-based vitamin D.

Fortified foods serve as primary dietary sources for most children. Cow's milk, both whole and reduced-fat varieties, is typically fortified with about 100 IU per 8-ounce serving. Many plant-based milk alternatives (soy, almond, oat) are also fortified, though amounts vary by brand. Some breakfast cereals, orange juice, and yogurt products contain added vitamin D.

Children in this age group should consume 2-3 servings of vitamin D-fortified milk or milk alternatives daily. If dietary intake seems insufficient, continued vitamin D supplementation of 400-600 IU daily is appropriate.

Safe sun exposure can contribute to vitamin D production, but parents must balance this with skin cancer prevention. For very young children, the American Academy of Dermatology recommends avoiding direct sun exposure for infants under six months. For older toddlers, brief periods of sun exposure—about 10-15 minutes several times per week on arms and legs—may help, though this varies significantly based on skin tone, geographic location, season, and time of day. Sun exposure should never result in burning, and protective measures remain important during extended outdoor time.

School-Age Children (5+ years)

Older children need approximately 600 IU of vitamin D daily. This age group often faces unique challenges, including decreased milk consumption as children prefer other beverages, increased time spent indoors with screen-based activities, and in some cases, limited access to nutritious foods.

Parents should encourage regular consumption of vitamin D-rich and fortified foods. Making fish a regular part of the family diet, choosing fortified products, and maintaining adequate dairy or fortified non-dairy alternatives all contribute to meeting requirements.

Physical activity outdoors should be encouraged not only for vitamin D production but also for overall health benefits. However, families living in northern latitudes face seasonal challenges, as winter sunlight may be insufficient for adequate vitamin D synthesis even with outdoor exposure.

For children at higher risk—those with dark skin, limited sun exposure, malabsorption conditions, or inadequate dietary intake—continued supplementation or periodic monitoring of vitamin D levels may be necessary.

Calcium: The Other Essential Component

While vitamin D often receives the most attention in rickets prevention, adequate calcium intake is equally important. Calcium provides the primary mineral building block for bones and teeth.

Recommended calcium intake varies by age: infants 0-6 months need 200 mg daily; infants 7-12 months require 260 mg; children 1-3 years need 700 mg; children 4-8 years require 1,000 mg; and older children 9-18 years need 1,300 mg daily.

Dairy products remain the richest calcium sources, with milk, yogurt, and cheese providing highly absorbable calcium. Non-dairy sources include fortified plant-based beverages, calcium-set tofu, canned fish with bones (like sardines), leafy green vegetables (though some contain compounds that reduce absorption), and fortified foods like certain cereals and orange juice.

Children who cannot or do not consume dairy products require careful dietary planning or supplementation to meet calcium needs. Parents should work with healthcare providers or registered dietitians to ensure adequate intake through alternative sources.

Special Considerations and At-Risk Populations

Certain groups face elevated rickets risk and require extra attention.

Exclusively breastfed infants without vitamin D supplementation represent a high-risk group, particularly if mothers are vitamin D deficient.

Children with darker skin living in temperate climates have significantly reduced vitamin D synthesis from sunlight due to higher melanin content. African American, Hispanic, South Asian, and Middle Eastern children may need year-round supplementation.

Premature infants have reduced bone mineralization at birth and increased nutrient requirements. They often need higher doses of vitamin D and calcium supplementation.

Children with chronic conditions affecting fat absorption (celiac disease, cystic fibrosis, inflammatory bowel disease) or those with kidney or liver disease may have impaired vitamin D absorption or conversion to active forms.

Children following restrictive diets—whether due to allergies, vegetarian or vegan lifestyles, or cultural dietary practices—may have limited access to vitamin D and calcium-rich foods.

Infants of mothers with vitamin D deficiency begin life with depleted stores and face elevated risk.

Working with Healthcare Providers

Regular well-child visits provide opportunities to assess rickets risk and discuss prevention strategies. Pediatricians should inquire about feeding practices, sun exposure, dietary habits, and family history.

For at-risk children, healthcare providers may recommend blood tests measuring 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels, the best indicator of vitamin D status. Levels below 20 ng/mL (50 nmol/L) are generally considered deficient, though optimal levels for bone health may be higher.

If rickets is suspected based on symptoms or risk factors, additional tests may include X-rays showing characteristic bone changes, blood tests for calcium, phosphate, and alkaline phosphatase levels, and assessment of parathyroid hormone.

Treatment for established rickets typically involves high-dose vitamin D supplementation (often 2,000-6,000 IU daily or higher under medical supervision), calcium supplementation if dietary intake is insufficient, and addressing any underlying conditions affecting vitamin D metabolism.

Practical Tips for Parents and Caregivers

Implementing rickets prevention doesn't require complicated interventions. Start vitamin D supplementation early for breastfed infants and don't wait for signs of deficiency. Keep supplements easily accessible as part of the daily routine—many parents give drops during a regular feeding or at a consistent time each day.

Choose vitamin D-fortified products when grocery shopping, checking labels on milk, plant-based alternatives, cereals, and other foods. Incorporate fatty fish into family meals at least twice weekly. Make outdoor play a daily priority when weather permits, recognizing the multiple benefits beyond vitamin D production.

If your child has darker skin or you live at northern latitudes, be particularly vigilant about supplementation, especially during winter months. For children following restricted diets, work with healthcare providers to ensure nutritional adequacy through appropriate food choices or supplementation.

Educate older children about the importance of vitamin D and calcium for strong bones, encouraging them to make healthy choices independently as they grow.

Looking Forward

Rickets remains entirely preventable through simple, cost-effective interventions. As awareness of vitamin D's importance grows and supplementation guidelines become more widely adopted, the incidence of this condition should decline.

Public health initiatives promoting vitamin D supplementation for all infants, education for parents and healthcare providers, food fortification programs, and addressing health disparities among at-risk populations all contribute to prevention efforts.

Parents and caregivers play the most crucial role in preventing rickets. By understanding risk factors, ensuring adequate vitamin D and calcium intake through supplementation and diet, and maintaining open communication with healthcare providers, families can protect their children from this preventable condition and support optimal bone development during these critical growth years.

The foundation for lifelong bone health begins in infancy and childhood. Taking simple preventive steps today ensures that children develop strong, healthy skeletons that will support them throughout their lives. With knowledge, attention, and appropriate supplementation, rickets can become truly a disease of the past.

Additional Resources:

Clear and concisely explained

ReplyDelete